Emacs with LaTeX for Academic Writing

Having a super powerful text editor can make your life much easier. There are quite a few out there, but there’s only that can do it all: Emacs.

In this post, I’ll outline how to get started with emacs. There are

plenty of tutorials out there, but I’d say that the best way to learn

is just to jump in. Thus, I will not spend a whole lot of time

describing what M-x does (the answer is everything). Instead, I’m

going to focus on introducing some of the more useful major modes (and

a minor mode or two) for working with LaTeX, markdown, R, and

git. We’ll also cover how to use knitr with LaTeX and rmarkdown in

emacs (this is how you have your code and words in the same

document).

Emacs is incredibly powerful, and ancient (in computer terms, anyway). Just to give you an idea of how old it is, it was invented before keyboards had arrow keys. Oh, and before Windows, Mac, or Linux existed as operating systems. So it can be a bit… weird, at times. For example, its built-in tutorial (which I recommend you never even look at) tells you that the best way to change lines is to use control-n or control-p (for next and previous). While this was probably more helpful when keyboards didn’t have arrow keys, it seems silly to me now. So what exactly is Emacs and why am I recommending it if it’s that old?

I have written before about what I look for in a text editor, but I’ll recap briefly here. In no particular order, here’s what I want:

- Cross platform

- Free and open source (at a minimum. preferably libre software)

- Syntax highlighting (for R, LaTeX, and rmarkdown)

- Code completion (for the above)

- Ability to send R code to console for evaluation

- BibTeX key completion

- git integration

A lot of people use one program do do some of these and a different program to do another. For example, you might use RStudio to work with R and a program like TeXStudio to write your LaTeX documents. I don’t think that there’s anything particularly wrong with that workflow, but it’s frustrating to me to have to constantly switch back and forth. Additionally, those programs tend to me rather limited in how you can configure them. If you want to do something that they don’t support, you’ll just have to wait for them to release that feature (assuming they release it at all). For that reason, I want a general-purpose program to edit text.

There are four big cross-platform text editors out there: Atom, Emacs, Sublime Text, and vim. Sublime is neither free nor libre. Atom is open source, but is still in its infancy, and really can’t do much that I need. So the choice is between vim and emacs. I chose emacs because it seems like there is a much bigger community emacs for the same sorts of things that I use it for. I think that vim can do most or maybe all of these, though, so if you give emacs a try and find it not to your liking, I’d suggest giving vim a go. So what exatly is emacs?

Emacs is a text editor, kinda. It can edit text, true, but it can also run tetris out of the box. Or, ya know, it can check your email, run twitter, or act as your file manager. Or pretty much anything else you might want it to do. More realistically, you might look at org-mode, which is a super powerful way of organizing a project and taking notes. I primarily use emacs to write documents (in LaTeX and/or rmarkdown), run R, and keep track of changes to those documents with git, although it’s slowly taking over other things that I do (like file management). In this blog post, I’ll briefly introduce how to get emacs to work the way we want it to.

Emacs thinks in terms of “modes.” It can have one (and only one) “major mode” active at any time, and any number of “minor modes.” So, for example, if you’re writing in markdown, you would have markdown-mode active as the major mode, and a few minor modes active for things like spell check and auto-complete. The first thing to do is to get emacs on your system.

Install Emacs

First, note that “Emacs” actually refers to a whole class of editors. The most popular is GNU Emacs, and that is the one I recommend. GNU Emacs is free and open source software with a huge development community.

-

Linux: For Ubuntu, you can just do

sudo apt install emacs24for a mostly up-to-date version as of this writing.1 Other linux distributions will be similar. -

Windows: For Windows, you can go here and download the most recent version ending in .zip. As of this writing, that is “emacs-24.5-bin-i686-mingw32.zip”. To use, you need to unzip the folder. There’s no installation necessary - just use the file there. To uninstall, just delete the folder.

-

Mac: For Mac, go here. Download and install like normal. If you use Homebrew, you can also get emacs through there, though it may not be as up-to-date.

MELPA

Emacs is super old, so it hasn’t always had the ability to manage your

packages for you through the internet.2 This was added relatively

recently, in fact. You’ll want to enable Emacs work with MELPA, which

is an online package archive. This is super easy - just follow the

instructions here. Note that

when it says to add to youre .emacs file, this is located at

~/.emacs.d/init.el for most operating systems3 (Windows may be

different) MELPA has a ton of packages - way more than you’ll ever want. I’ll walk though

some of the most important here, though.

If you’re using emacs for the first time, I recommend you stop reading

for a moment and go play around with emacs. Try to configure your

.emacs file a little bit. You can do M-x package-list-packages

(the M-x says to hold the alt key and tap x. Then type “package-list-packages”) to

see all the available packages. Emacs has a lot of settings that are

not good out of the box, and several packages aim to fix this. Try

installing and loading the

better-defaults

package. Several other helpful packages are listed

here. You can also

look at my .emacs file for an

idea of what to do.4

The rest of this post will assume that you’re at least vaguely familiar

with how emacs works. If you’re still having trouble getting emacs to

do something, try using google and if that fails, there’s always

stackoverflow. Note

in particular I’m assuming that you’re at least vaguely aware (if not

totally comfortable yet) with emacs’ convention of using C- and M-

to denote holding the control and alt (or option) keys for the various

keybindings. Keybindings are what most other programs refer to as

shortcuts. Since all emacs keybindings are commands, you don’t

actually have to learn any of them - M-x will let you type in any

command you want. But they will make your life a ton easier!

Using LaTeX

The package you want to use for working with LaTeX is called “AuCTeX.”

It has a website here, but you

can just get it through MELPA. Honestly, using AuCTeX to work with

LaTeX is a breeze. There are a few keybindings (keyboard shortcuts)

that will make your life easier, but most of them are

optional. Perhaps the most important is C-c C-c, which will begin to

compile your LaTeX document. It’s smart enough to figure out what the

next step in compiling your document is, so for example if you need to

run pdflatex, then biber, then pdflatex, and pdflatex, then view

your pdf (if you need to look up why you might need to run those

commands that way, this post won’t cover them.), it will run through

all of those things in the correct order.

Other than that, there isn’t much that you need to know about AuCTeX. There is a really good stackexchange answer that goes through the most common keybindings you’ll need.

Using R

Emacs can play very nicely with R (or Stata) through Emacs Speaks

Statistics, commonly called ESS. You can

download it from MELPA, but it causes issues for me if I do it that

way (no idea why)5, so I download and install it from Ubuntu’s

repositories with sudo apt-get install ess. For Mac and Windows

users, you can try it through MELPA or through the instructions on the

ESS website.

ESS makes emacs play very nicely with R. You can enable “font

locking,” which is emacs-talk for syntax highlighting. It has several

nice keybindings as well. For example if you’re in an R script, C-RET (control-return on most

keyboards) sends the current line to R for evaluation. Similarly, C-c

C-c sends a whole region to R for evaluation. You can find the whole

list of key bindings (shortcuts)

here.

Reference Management

Emacs is simply amazing at dealing with references. There is a “minor mode” called RefTeX that is like a godsend for reference management. There are two ways for RefTeX to find your .bib file:

-

You can set up a default .bib file via your

.emacsfile. So you can set the reftex-default-bibliography variable like so:(setq reftex-default-bibliography '("path/to/bibfile.bib"))where you replacepath/to/bibfile.bibwith the path on your system. You can also have multiple bibliographies there, since it is a list. -

RefTeX should automatically find your .bib file through the

\bibliography{}(or similar) LaTeX command. So if you’ve set up your bibliography in your LaTeX file, RefTeX should find it.

Note that you can use either the first or the second way, but not both.

Once you have that set up, you need to turn on RefTeX (which is a

minor mode) in AuCTeX. Just search google for how to do this; it’s

relatively easy. You can also take a look at my .emacs file

on Github, which should give you

an idea of what you need to do.

Once you’ve got that down, you’re good to go! Just start up emacs, and

open up a .tex file (make sure that AuCTeX is the major mode and that

RefTeX is active as a minor mode). The keyboard shortcut for a

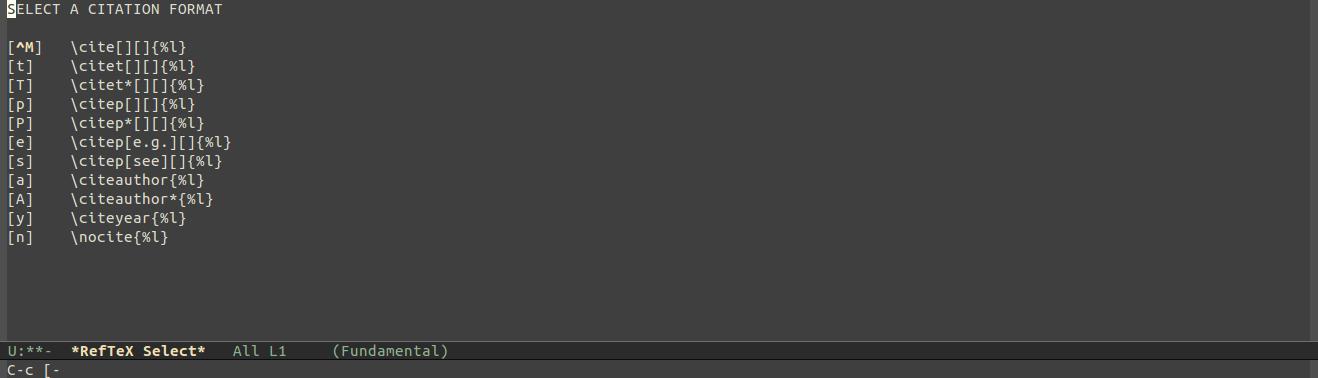

citation is C-c [. This will bring up a menu that looks something like this[^refdefault}]:

As you can see, these are all the different citation formats. So, if

we want the \citep{} command, we simply press p. At that point, we

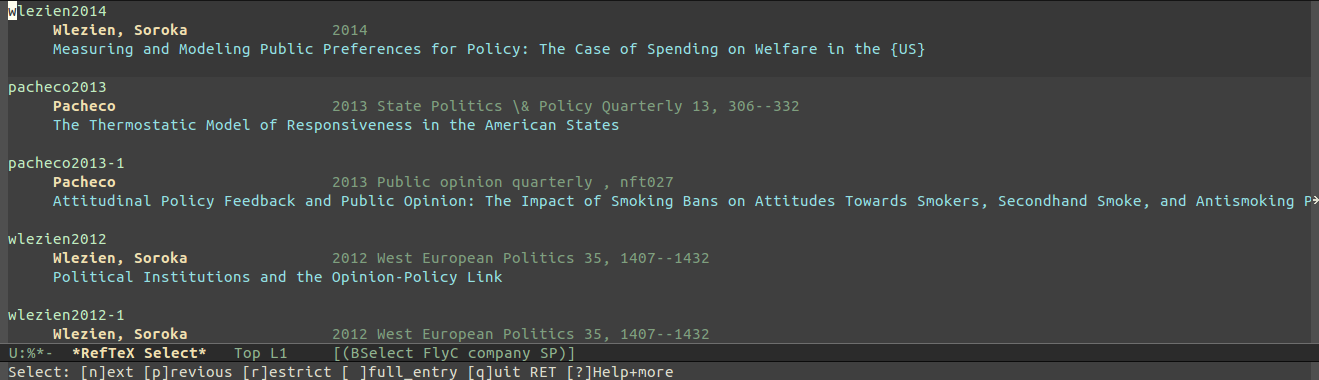

can put in a search term and RefTeX will search through our .bib file

for matches. You can search for authors, titles, etc. So for example,

if I am looking for something to do with policy, but I can’t remember

the authors, I just type in “policy” and press enter (return). RefTeX

will then look through my .bib file and return any matches it sees.

This will look something like this:

I can navigate through the listings to select the one that I want. Once I’m on it, hitting enter will automatically insert the selection into my tex file.

If I’ve searched for something too broad (“policy”, for example) and

need to narrow the search, I can press r to search inside my

results. So if I was interested in policy pieces that Erikson has

written, I can just type “r Erikson” and it will narrow the choices to

just those pieces that mention both policy and Erikson.

And that’s it! RefTeX is a pretty powerful tool. It can also handle more advanced features, like keeping track of your other references in your document (like Equations, Figures, Tables, etc).

Git

I’ve already posted a bit about the

wonders of git. Emacs works wonderfully with git through the package

magit. It’s available through MELPA, so install it however you

like. The most useful command is M-x magit-status, which is kind of

the “starting point” for all things git. I assign that to two

different key bindings (mostly because if I only assign it to one I

can’t remember which!): C-c g and C-x g.

From there, you can begin a commit with c, which will pull up a

whole bunch of options. For a normal commit, just hit c again, which

will let you type the commit message. Once you’re done typing, C-c

C-c commits.

From the magit-status screen, you can press

b to see options relating to branching. z will pull up stashing

options. y will pull up a branch manager. There’s a nice cheatsheet of the most common actions for

magit here.

Knitr and rmarkdown

Finally, you want to be able to combine your code for analysis and

your document. You can do that in emacs, of course. You’ll want the

package called polymode. Long

story short, this package allows you to have different major modes

active in your document depending on different points. So, for

example, if you want to combine R code and LaTeX in a .Rnw document,

polymode will allow you to use LaTeX-mode when writing the document,

then R-mode within the <<>>= ... @ markers.

Super useful minor modes

A lot of emacs’s power comes from the major mode that you’re in. AuCTeX can do everything that you need for LaTeX files, for example. ESS is in charge of statistics, and polymode lets us have the best of both of those worlds. However, having a few minor modes active can make your life much easier. Here’s a short list of some of the more useful minor modes I use:

smartparens: makes it easier to maintain balanced parenthesescompany: autocompletes all the things! Especially useful for remembering function names and variable names in R, but also useful for typing difficult-to-spell words. There are a lot of different packages that plug into company. You can checkoutcompany-statistics,company-auctex, and some others.flycheck: checks your code for syntax errors and good style on the fly. To use with R, you’ll need thelintrpackage available on CRAN. Get it withinstall.packages("lintr")flyspell: same concept asflycheck, but for spellingauto-fill: makes test wrap lines at a reasonable length. Also note that this makes actual new real lines rather than just wrapping the test. This is especially useful for git, which thinks in lines of code.font-lock: This is emacs’s weird way of referring to syntax highlighting

-

If you really want the bleeding edge, you can use the ppa here. ↩

-

Remember, emacs is older than the internet, at least in the form that we know it today. ↩

-

Emacs may not have created this file when it installed. Go ahead and create it manually. ↩

-

Note that I use the

use-packagepackage in order to make it easier to tote around my .emacs file. So if you want to use it, you’ll also need to install it andrequireit as specified at the top of my init.el file. ↩ -

In particular, polymode will not work properly with rmarkdown files. It can’t start r-mode properly inside the r-code sections. If you have any idea why this is or how to fix it, I’d love to hear! ↩